It’s interesting that we mark the beginning of a new year just after the moment in time of the longest day of the year and the beginning of winter. I always think of new as being that which occurs in the spring – dandelions and periwinkle poking color up amidst the brown of dead leaves, the soft green gray hues of the forest that come alive in morning mists still chilled by winter, and water still running cold and fast through the woodlands of my hollow.

It’s interesting that we mark the beginning of a new year just after the moment in time of the longest day of the year and the beginning of winter. I always think of new as being that which occurs in the spring – dandelions and periwinkle poking color up amidst the brown of dead leaves, the soft green gray hues of the forest that come alive in morning mists still chilled by winter, and water still running cold and fast through the woodlands of my hollow.

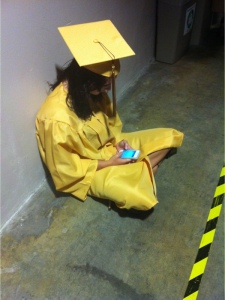

Yet, I cannot escape that for many decades the sign of a new year that brings a real focus on new to me begins with the school bus that picked me up and dropped me at the end of my family farm’s half-mile long, sugar-sand road in the Low Country. The buses are still yellow, and the seats are still the basic same shape as they were six decades ago. Technology has eliminated the driver having to manually open and close the bus doors and side stop sign. But, kids still make a lot of noise on the bus, fight over the window, and love drivers who smile and take time with them.

The school bus year begins and ends in summer light. I’ve ridden buses, driven a bus, supervised buses, and been responsible as a school superintendent for the safety of thousands of students riding almost 15,000 miles every day of the school year. In that role, as I have ridden each year on a bus to pick up children early on their first-day morning rides, I’m reminded in each of my school bus years that each new year’s ride brings a wonder at the lives and dreams of thousands and thousands of children who have traveled with me as learners over all the years that I have been in schools – four-plus decades of learners coming and going from classrooms and schools that I have tended in my own work to nurture spring-time into the lives of children, to help them grow from their hopes and dreams in a new year.

The school bus year begins and ends in summer light. I’ve ridden buses, driven a bus, supervised buses, and been responsible as a school superintendent for the safety of thousands of students riding almost 15,000 miles every day of the school year. In that role, as I have ridden each year on a bus to pick up children early on their first-day morning rides, I’m reminded in each of my school bus years that each new year’s ride brings a wonder at the lives and dreams of thousands and thousands of children who have traveled with me as learners over all the years that I have been in schools – four-plus decades of learners coming and going from classrooms and schools that I have tended in my own work to nurture spring-time into the lives of children, to help them grow from their hopes and dreams in a new year.

In my years in education, I’ve experienced the amazing freedom to create, early on free from the constraints of accountability testing run amok back in those days in the seventy and eighties when kids mostly read and did math and tests were administered for different purposes. Schools were not perfect then. They never have been. But kids in the school where I worked were the first generation of middle schoolers to read novels, not basal readers.

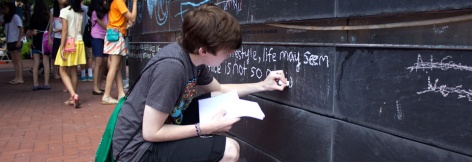

I remember a group of children, a few dad carpenters, and the teacher constructing a subway platform in a room so the classes could vicariously experience a slight feel of New York in a small rural county in Virginia. The teacher, Lynn, understood that children needed context for what they read and she was committed to recreating her classroom as the novel., Slake’s Limbo. The children painted their own graffiti as they listened to the sounds of the subway she had captured on cassette tapes during a visit to the city. It wasn’t New York but with walls covered with black paper, a raised platform overlooking faux rails, and sounds of trains coming and leaving, it was not a classroom of desks and chairs – hard work for Lynn but she always put in her best effort to create a real learning experience for kids.

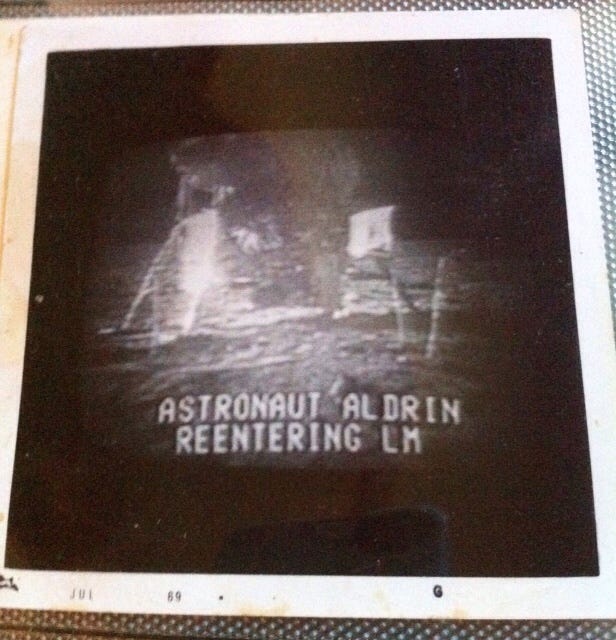

We took kids on adventures, some who had never seen the ocean or been more than a few miles from the county seat to explore natural caves and quarries and fossil pits in West Virginia and to the ocean to experience marine biology and earth science wading through the waves and marshes and walking the beaches of coastal Virginia. We came back to the school at night to set up a telescope for kids to look at the moon and visible planets, and once even a lunar eclipse. I don’t even know how we paid for the trips other than through a federal grant received when environmental education became a national focus as the nation began to process the impact of air pollution over LA, nuclear accidents and chemical spills in the northeast, and the degradation of forests and erosion of lands all over fifty states.

We took kids on adventures, some who had never seen the ocean or been more than a few miles from the county seat to explore natural caves and quarries and fossil pits in West Virginia and to the ocean to experience marine biology and earth science wading through the waves and marshes and walking the beaches of coastal Virginia. We came back to the school at night to set up a telescope for kids to look at the moon and visible planets, and once even a lunar eclipse. I don’t even know how we paid for the trips other than through a federal grant received when environmental education became a national focus as the nation began to process the impact of air pollution over LA, nuclear accidents and chemical spills in the northeast, and the degradation of forests and erosion of lands all over fifty states.

We worried less about teaching facts then and there was no teaching to a test because we were living in the inquiry generation of science educators, trained through post-Sputnik era funds to engage learners and create paths for them to solve their way through problems rather than delivering all the answers to them. The goal was to educate all children in science and maybe a few might become physics majors for NASA and a few might even become science educators. In our country school, we were well aware of the differences in circumstances of life and we weren’t that far past segregation in the South and even IDEA was a newly minted public law (94-142) that brought children to school who had never been in school before. We were very fortunate to be led by administrators who were in the work to support the learning that children would get from us and not simply to manage the school.

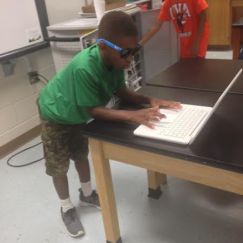

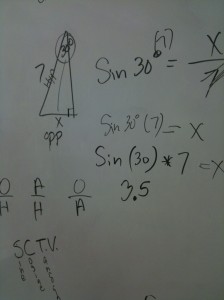

In those days, teachers could take time to slow down and have a discussion with kids about topics that were off topic – sometimes because kids just wanted to distract us and sometimes because they simply had great, curious questions and interests worth exploring. I was expected to plan deeply for the units I would teach and in that era worked in a school faculty expected to use Bloom’s Taxonomy as a framework for considering what kids would be able to recall, understand, apply, synthesize, and evaluate in their learning – not just surface but what we label today as deep to transfer learning. We also were expected to design assessments prior to teaching a unit and, in science, those assessments weren’t just paper pencil but also included hands-on responses to physical tasks – after all, it’s hard to demonstrate on paper alone that you can measure, titrate, or use a plant key to evaluate whether a leaf is a sycamore or a tulip poplar.

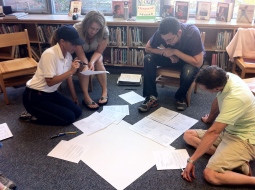

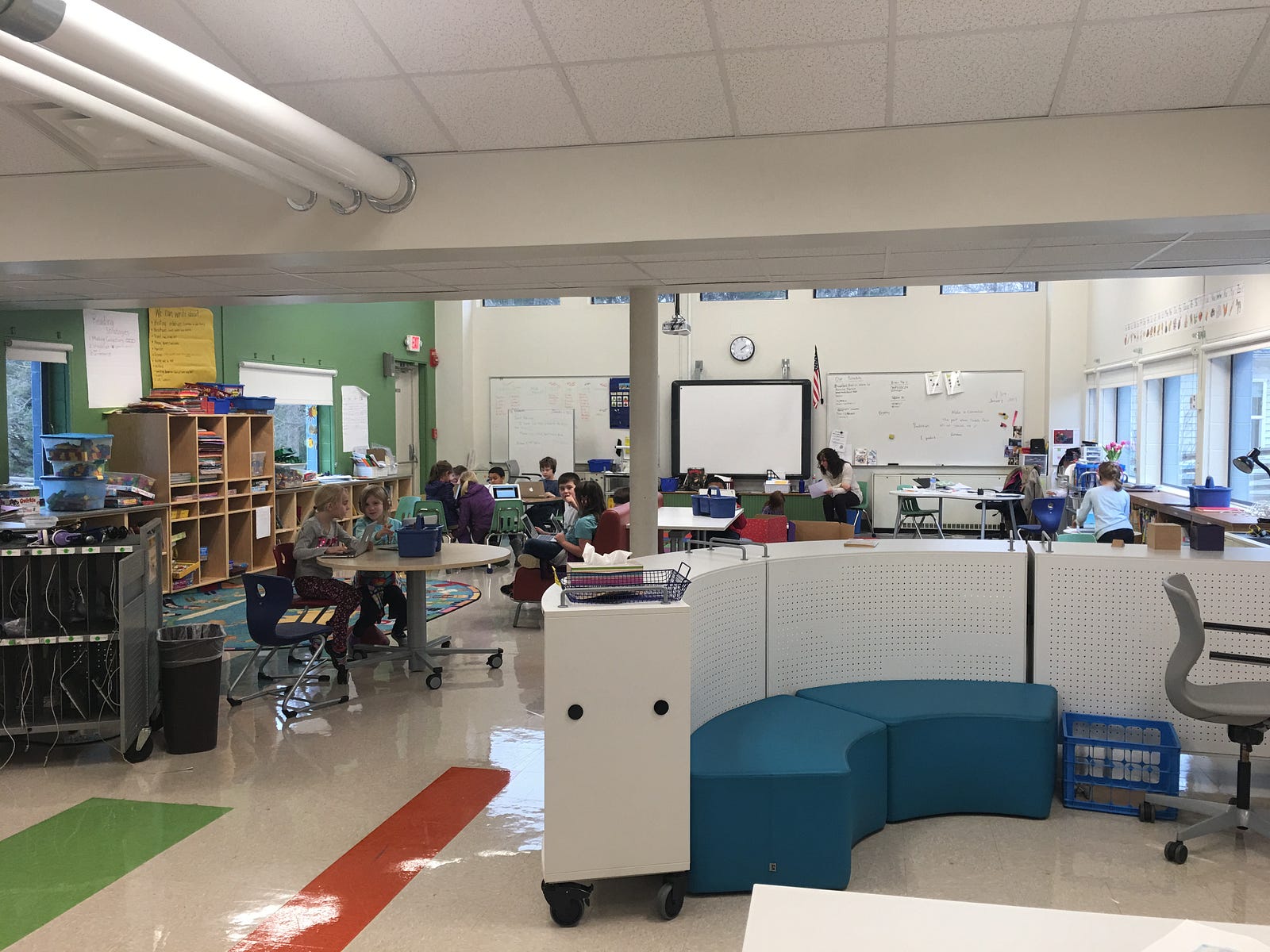

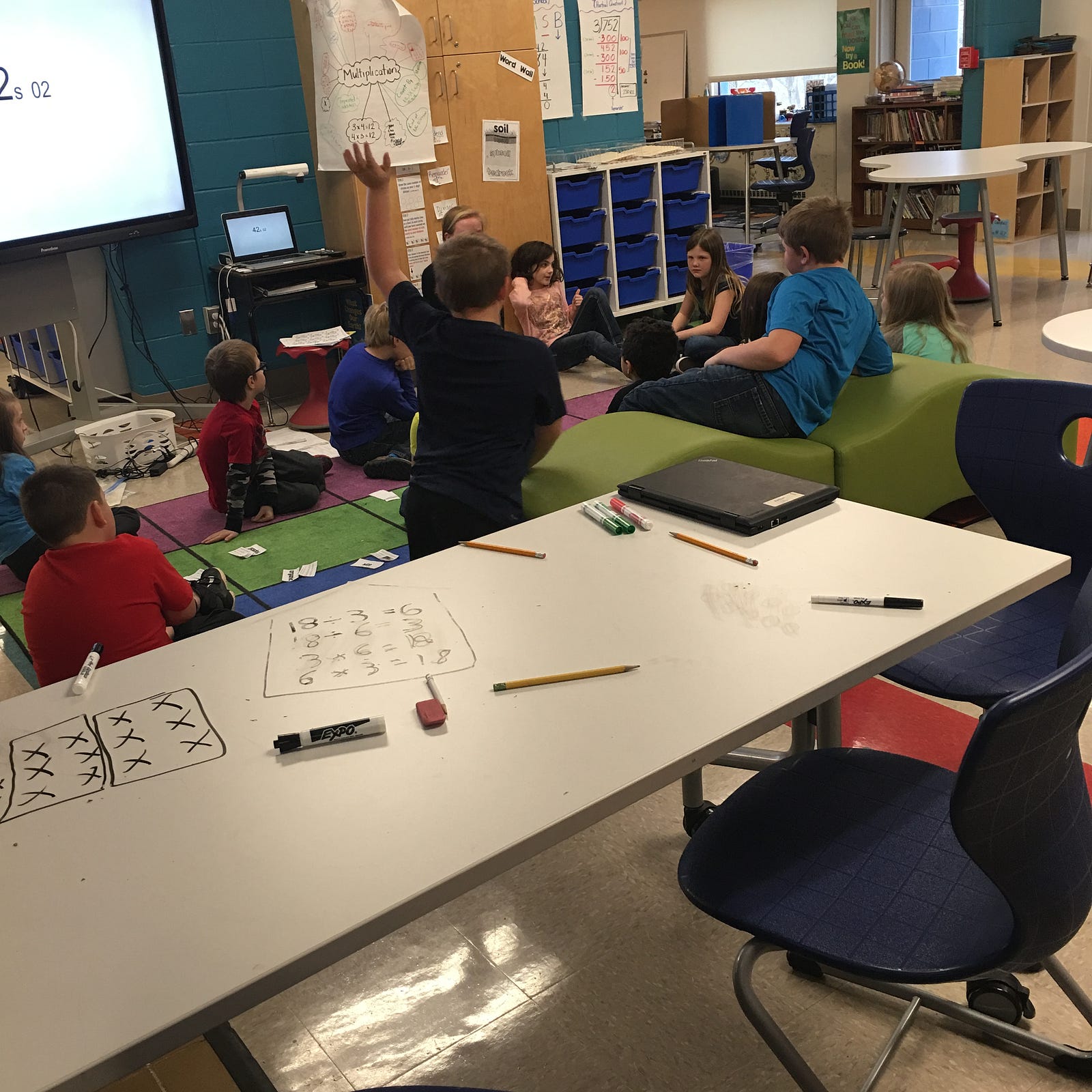

My co-teaching partner and I ran learning stations in our connected classrooms and the students we served rotated through stations working together and individually on a variety of centers designed to provide different ways to process what they were learning. We thought we were pretty cool because we used a small film loop media station, listening centers, lab activities, and reading areas. One center might involve looking at blood circulation under a microscope in the tail of a goldfish wrapped in soft very wet cotton (for a very few seconds) while another could be a simple lab to extract chlorophyll from leaves. Sometimes, kids had to go somewhere in the building or outdoors to accomplish learning that involved observations and journal writing. Or, perhaps to count how many kids didn’t eat cooked carrots served on the cafeteria line and ask them and record why not.

There was method in our teaching madness and most of the time kids were doing active learning work while my partner and I circulated, sometimes running a demo or teacher-assisted mini-lab that had safety risks or going over important concepts with small groups of kids. Kids were often learning to apply math including early algebra and to read for meaning and write for understanding. Cross-curricular connections were considered important and grade level team meetings focused on how to make more of those happen.

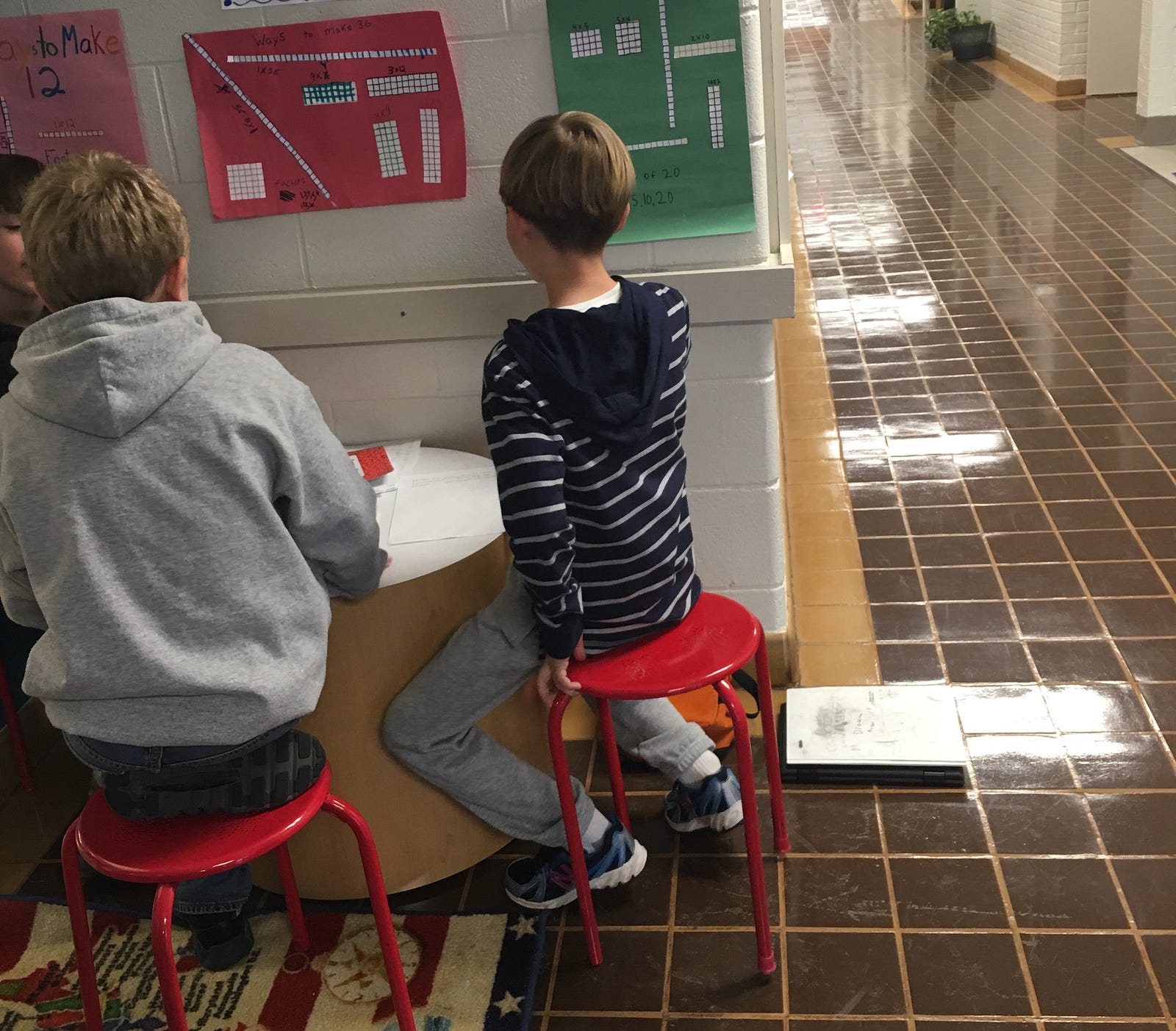

Inquiry meant asking questions, making predictions, testing, experimenting, discussing, and reporting on what was learned. It wasn’t always easy to have kids land in the learning zone we had targeted but we tracked their progress as they tracked their own, recording progress, questions, and their notes in daily learning logs. We actually had time to talk with individual kids as we circulated, to see their excitement when they exhaled into a BTB solution and observed the beaker of liquid turn from blue to yellow. And, then to hear them ask why and begin to make suggestions to each other.

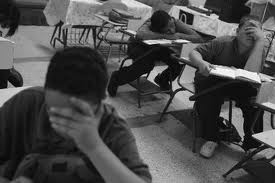

In those minutes of watching and observing learners, I saw kids in those days of inquiry learning who were curious, interested, engaged, and empowered – not about everything, or in every class, but kids just weren’t sitting motionless at desks in our classes in that school listening all the time to teachers, or filling out work sheets, or taking practice tests, or reading from textbooks. It’s not that those things didn’t happen but they weren’t the dominant form of work that kids did in our science classes. We also didn’t sort and select kids or group them for work or even assign seats since we expected them to be independent and interdependent as they accomplished work together and moved routinely around two rooms.

I didn’t master this kind of teaching alone my first year but with the help of three other partner teachers, all with experience and all who were NSF trained in teaching through science inquiry. However, within three years of working (with no planning period and lunch daily with a class of kids in my room due to severe overcapacity enrollment kind of like walking uphill to school in the snow), I felt far more confident in my capability to move kids to think, ask good questions, manipulate variables, solve for unknowns, use lab equipment appropriately, and to hold their own in discussions with each other.

These great kids who also helped teach me how to be a teacher are in their fifties today with grandchildren who are in or already graduated from high school. When I occasionally run into one of them, they remember the field trips, the active work they did, and even reference the content, sometimes with a question about something they had done. But the most satisfying, even poignant comment I’ve heard was from a for profit package delivery supervisor who I ran into at the grocery store one day, “We had fun in school, I wish my own kid had that kind of fun in school.”

When I walk away from my role as superintendent at the end of this school year for family reasons, I don’t expect to leave the profession behind in totality. I’ve never imagined that I could be happier doing anything other than being an educator – although some free time to garden, read on demand, and not spend so many evenings in night activities does have its curb appeal. However, I can’t imagine life without a first day of school or time in a library or classroom reading to children or helping out as an extra pair of hands in the cafeteria. I expect I’ll volunteer a bit.

When I walk away from my role as superintendent at the end of this school year for family reasons, I don’t expect to leave the profession behind in totality. I’ve never imagined that I could be happier doing anything other than being an educator – although some free time to garden, read on demand, and not spend so many evenings in night activities does have its curb appeal. However, I can’t imagine life without a first day of school or time in a library or classroom reading to children or helping out as an extra pair of hands in the cafeteria. I expect I’ll volunteer a bit.

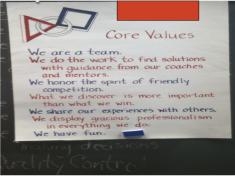

I’ve spent time over this winter holiday taking stock of a career filled with life’s lessons. I have learned across decades from educators, parents, and children that relationships matter more than anything else in our learning communities. Our voices have the power to hurt or heal and when we focus on finding common ground to solutions, we are more likely to walk away from our time together seeing the strengths of others, not their deficits.

I’ve also learned that no matter what standards or lessons we are expected to teach, whether as in my first years of teaching with inquiry as the end in mind or in the more mass standardized model of today’s test-objectified classrooms, it’s often the unintended opportunities that become the most influential learning experiences our children will get because of us. That’s why when a teacher said to me a few years ago, “Pam, I get frustrated when kids want to stop and talk about what really caused the American Civil War and not just take down notes – and I feel compelled to reply that we don’t have time.”

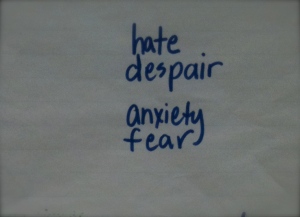

The time to pause and explore big ideas through the questions and curiosities of kids may be the greatest loss to learning that resulted from the reform movement that began in the 1980s and continues still today. The data are in and our kids today are less creative and less critical in their thinking than they were decades ago. Some think entertainment technologies are to blame and, yes, kids have been pulled away from play and active experiences by devices. But, as an educator who has lived through decades of mass standardization of rote learning, I, along with these empirical researchers, have to put that at the top of the list because the reform accountability movement began long before smart devices became common in the hands of children.

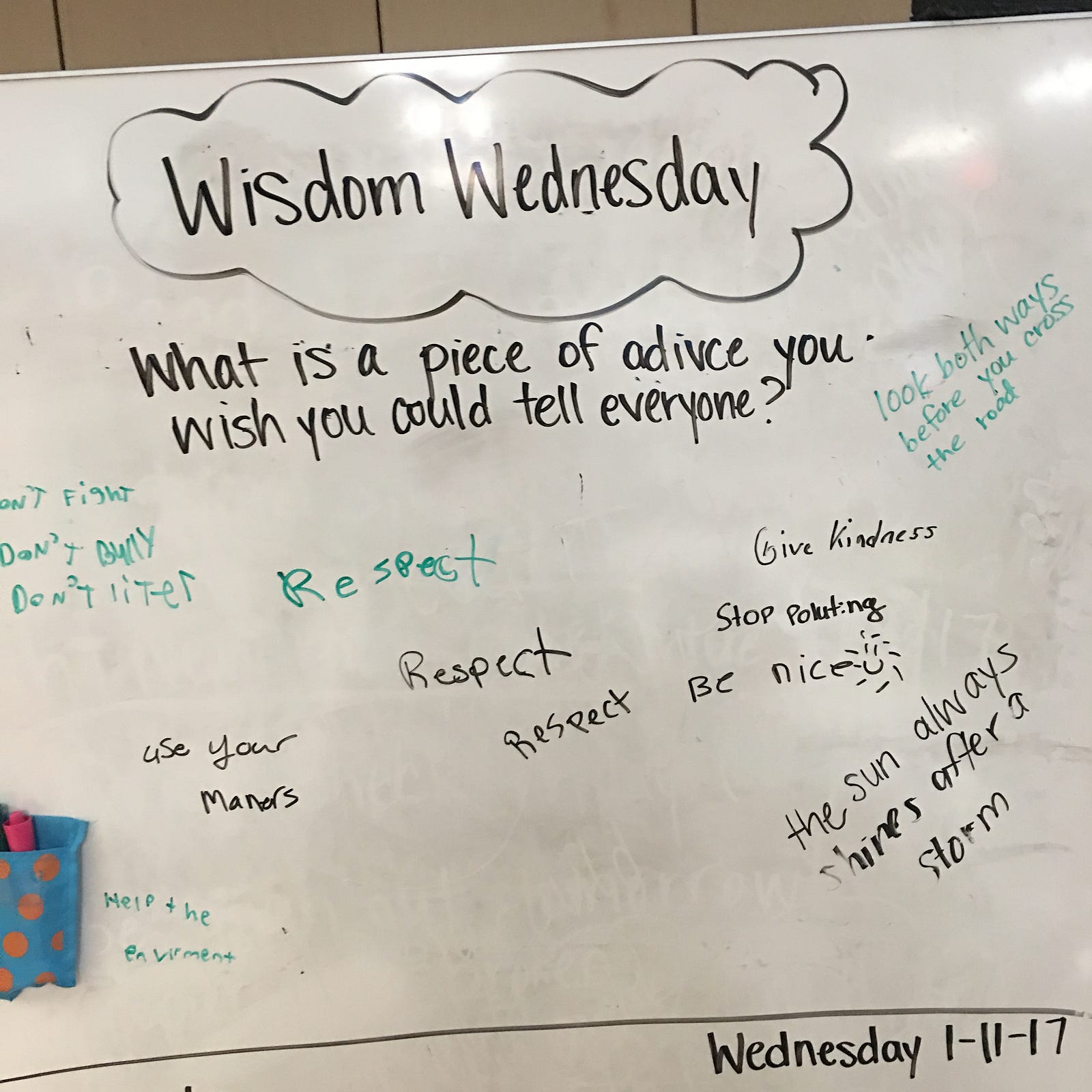

My advice to the social studies teacher that day and to others with similar concerns, knowing that I bear a different level of responsibility for test scores as superintendent than a classroom teacher does, “Take the time. There’s more to educating kids for life than just passing a state test. Learning to question, discuss, debate, defend, and listen to others’ perspectives is worth it’s weight in gold long after kids have forgotten the starting date of the Battle of Gettysburg. And, no state multiple choice test is going to measure those critical thinking skill sets.”

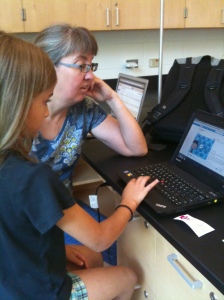

Reductions in state testing in Virginia has occurred because parents, teachers, and politicians have realized that the over-emphasis on testing has removed much of life from learning in our schools. There’s a renewed interest in learning that has a stickiness beyond the temporary effect of test-prepping for the multiple choice tests that have permeated the lives of our young millennial teachers when they were students in school. I hope this younger generation of educators rejects the quick test to learn model and invests in using practices that build deep learning; project-focus, inquiry, labs, case studies, seminar discussions, observation and journal writing and so much more that can be done today to help kids become researchers and owners of their own learning. With Internet access today, we can take kids so much farther than the primitive technologies of my first years of teaching did and as a resource tool it expands the repertoire of excellent teaching possibilities far beyond what I had available to me in my teaching years.

Finally, in my reflective wanderings over this break, I also find I hold firm to a belief that restoring slow time to the learning process can lead us to …

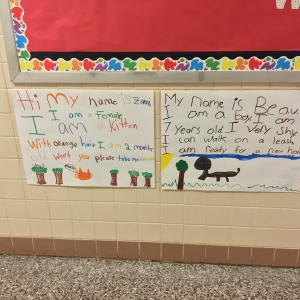

school as an inspiring space for learning that promotes curiosity, questions, interests, and passions about everything from humanities to STEM to arts to wellness to languages of all kinds and,

to helping kids learn what they want to learn not just what we want them to learn and,

to finding positive relationships grounded in the strengths of a diverse community and,

to facilitating and coaching kids to work and learn together rather than mostly in isolation of each other.

Perhaps if we do these things, we have a shot at hooking kids on learning for life, not just to pass tests.

It’s interesting that we mark the beginning of a new year just after the moment in time of the longest day of the year and the beginning of winter. I always think of new as being that which occurs in the spring – dandelions and periwinkle poking color up amidst the brown of dead leaves, the soft green gray hues of the forest that come alive in morning mists still chilled by winter, and water still running cold and fast through the woodlands of my hollow.

It’s interesting that we mark the beginning of a new year just after the moment in time of the longest day of the year and the beginning of winter. I always think of new as being that which occurs in the spring – dandelions and periwinkle poking color up amidst the brown of dead leaves, the soft green gray hues of the forest that come alive in morning mists still chilled by winter, and water still running cold and fast through the woodlands of my hollow. The school bus year begins and ends in summer light. I’ve ridden buses, driven a bus, supervised buses, and been responsible as a school superintendent for the safety of thousands of students riding almost 15,000 miles every day of the school year. In that role, as I have ridden each year on a bus to pick up children early on their first-day morning rides, I’m reminded in each of my school bus years that each new year’s ride brings a wonder at the lives and dreams of thousands and thousands of children who have traveled with me as learners over all the years that I have been in schools – four-plus decades of learners coming and going from classrooms and schools that I have tended in my own work to nurture spring-time into the lives of children, to help them grow from their hopes and dreams in a new year.

The school bus year begins and ends in summer light. I’ve ridden buses, driven a bus, supervised buses, and been responsible as a school superintendent for the safety of thousands of students riding almost 15,000 miles every day of the school year. In that role, as I have ridden each year on a bus to pick up children early on their first-day morning rides, I’m reminded in each of my school bus years that each new year’s ride brings a wonder at the lives and dreams of thousands and thousands of children who have traveled with me as learners over all the years that I have been in schools – four-plus decades of learners coming and going from classrooms and schools that I have tended in my own work to nurture spring-time into the lives of children, to help them grow from their hopes and dreams in a new year. We took kids on adventures, some who had never seen the ocean or been more than a few miles from the county seat to explore natural caves and quarries and fossil pits in West Virginia and to the ocean to experience marine biology and earth science wading through the waves and marshes and walking the beaches of coastal Virginia. We came back to the school at night to set up a telescope for kids to look at the moon and visible planets, and once even a lunar eclipse. I don’t even know how we paid for the trips other than through a federal grant received when environmental education became a national focus as the nation began to process the impact of air pollution over LA, nuclear accidents and chemical spills in the northeast, and the degradation of forests and erosion of lands all over fifty states.

We took kids on adventures, some who had never seen the ocean or been more than a few miles from the county seat to explore natural caves and quarries and fossil pits in West Virginia and to the ocean to experience marine biology and earth science wading through the waves and marshes and walking the beaches of coastal Virginia. We came back to the school at night to set up a telescope for kids to look at the moon and visible planets, and once even a lunar eclipse. I don’t even know how we paid for the trips other than through a federal grant received when environmental education became a national focus as the nation began to process the impact of air pollution over LA, nuclear accidents and chemical spills in the northeast, and the degradation of forests and erosion of lands all over fifty states.

When I walk away from my role as superintendent at the end of this school year for family reasons, I don’t expect to leave the profession behind in totality. I’ve never imagined that I could be happier doing anything other than being an educator – although some free time to garden, read on demand, and not spend so many evenings in night activities does have its curb appeal. However, I can’t imagine life without a first day of school or time in a library or classroom reading to children or helping out as an extra pair of hands in the cafeteria. I expect I’ll volunteer a bit.

When I walk away from my role as superintendent at the end of this school year for family reasons, I don’t expect to leave the profession behind in totality. I’ve never imagined that I could be happier doing anything other than being an educator – although some free time to garden, read on demand, and not spend so many evenings in night activities does have its curb appeal. However, I can’t imagine life without a first day of school or time in a library or classroom reading to children or helping out as an extra pair of hands in the cafeteria. I expect I’ll volunteer a bit.

I remember talking a few years ago to a teacher who was concerned about a middle school student who was upset because he’d been excluded from reading a book he wanted to read in a book group because of his learning disability. The teacher commented that he just couldn’t read the text and so he had been placed in a less sophisticated book. I was just on the front end of processing background on universal design for learning and asked her if he could listen to the text since he would have no problem handling the cognitive challenge of the content. She replied, “but listening is not real reading.” Quite frankly, I didn’t know what to say. I myself had begun to listen to audio books in the car and felt when I finished a book I had indeed “read” it (for the record I’m a lifelong voracious text consumer which seems to be worth less and less as we move into the Machine Age.) I walked away thinking we have to challenge our definition of what it means to be a reader – and what it means to be labeled as learning disabled.

I remember talking a few years ago to a teacher who was concerned about a middle school student who was upset because he’d been excluded from reading a book he wanted to read in a book group because of his learning disability. The teacher commented that he just couldn’t read the text and so he had been placed in a less sophisticated book. I was just on the front end of processing background on universal design for learning and asked her if he could listen to the text since he would have no problem handling the cognitive challenge of the content. She replied, “but listening is not real reading.” Quite frankly, I didn’t know what to say. I myself had begun to listen to audio books in the car and felt when I finished a book I had indeed “read” it (for the record I’m a lifelong voracious text consumer which seems to be worth less and less as we move into the Machine Age.) I walked away thinking we have to challenge our definition of what it means to be a reader – and what it means to be labeled as learning disabled.

I think

I think  s a result, she became a social entrepreneur, creating not just a bridge-building camp for middle school girls but one in which participants give back to our community by creating bridges that make our local walking trails accessible.

s a result, she became a social entrepreneur, creating not just a bridge-building camp for middle school girls but one in which participants give back to our community by creating bridges that make our local walking trails accessible. And, there’s

And, there’s  Finally, there is

Finally, there is

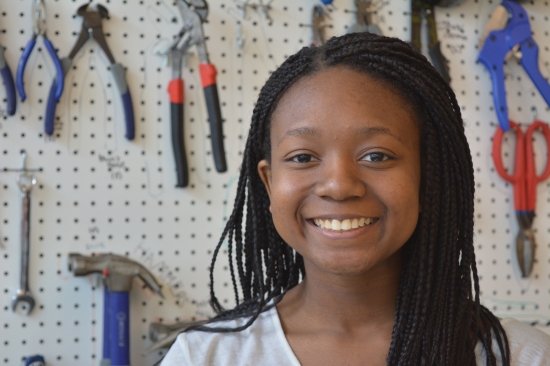

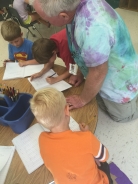

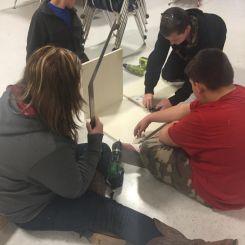

Here’s what I discovered when I visited the cafeteria. Middle schoolers were scrambling all over the tree houses. I could only think that maybe this getting to yes philosophy does have limits. Then I stepped back to observe the kids working under Alex Gilliam’s watchful eye. They were a diverse mix representing all the demographics of their tiny middle school. But what really caught my attention was their joy in designing and building, using saws, and drills, and hammers like pros.

Here’s what I discovered when I visited the cafeteria. Middle schoolers were scrambling all over the tree houses. I could only think that maybe this getting to yes philosophy does have limits. Then I stepped back to observe the kids working under Alex Gilliam’s watchful eye. They were a diverse mix representing all the demographics of their tiny middle school. But what really caught my attention was their joy in designing and building, using saws, and drills, and hammers like pros.