He wouldn’t have done well on the Impulsivity Test for children on Angela Duckworth’s webpage, but I think he was the grittiest kid I ever saw come through the elementary school where I was principal.

He’d had a horrific young life by the time he was nine – and he walked through the door angry on the day that his latest foster-mother registered him well after school was underway that year. The folder forwarded by his former school was thick with school changes, the worst of grade reports, and assessments by all kinds of professionals who’d been charged to take a look at him based on referrals of one sort or another. He was tough. His first words to me? “I hate this f’ing school.” He’d been there all of five minutes.

I noticed that his blue eyes constantly darted sideways to check out the people in the room. I knew that look. I could feel his intensity almost as heat rolling off his rail thin body and I think today I understood even then that beneath his anger lived a depth of real fear. He was just a child. He was a survivor.

When I first read his records, it was obvious why he was hostile to adults specifically, but others in general. His nuclear family had self-destructed around him and he’d been a tiny victim of that ugliness. Enough said. By the time he reached us, he’d seen at least 16 different home placements, including at least one brief stint in a residential home. He ran through them in a litany one day for me as if he was reciting the alphabet. He showed no emotion.

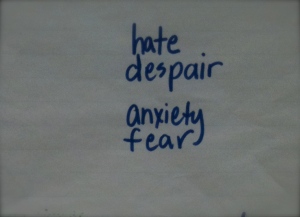

I placed him with the best teacher I had and hoped that he would settle down and find a peace that would allow him to learn. He tested below grade level which was consistent with his records, but his new teacher saw capability within him. He loved science. He hated math. He discovered a love of writing with her. He thought books “sucked.” When his teacher shared an intense poem of his with me, it was obvious he wasn’t writing subdivision poetry. There were no rainbows or cute puppies in his young life. His words were ones of abandonment.

He didn’t do homework unless his foster-mother made him and it was war at the kitchen table from the stories she shared. We created sign-off logs and contracts, offered extra time shooting hoops with a male assistant, and checked in with his foster-mother routinely. He turned in next to nothing. But he finally found a bit of a passion when he got into building simple circuits and figured out all kinds of cool things he could do with bulbs and batteries. When he wasn’t fiddling at a science center, he wrote about hating his family and foster siblings or stared out the window. He had no safety net. And, he was nine years old. A prior assessor had labeled him as a slow learner. But, none of us thought that at all when he forgot long enough that he lived in a child’s version of hell to show that he was a curious, interested kid who loved to learn.

He’d end up yelling at someone in school pretty much every day. Sometimes the teacher. Sometimes other kids. Sometimes … me. Once I invited him to come for a “lunch-bunch” Wednesday in my office and to bring some classmates. He invited no one. He came and wandered my office, picking up science gizmos I kept for just that purpose. He was intrigued with my framed black rattlesnake skin hanging above my desk and wondered if I’d shot it. I told him no that it had been found by a friend – a roadkill in New Mexico. Because I loved snakes, I told the boy the story of how I acquired that skin. My desktop computer caught his attention and he wanted to know if he could type on it. I let him do that a bit and I remember the delete key mesmerized him – he typed his name and deleted it over and over again. These were pre-laptop days, pre-video game days, pre-almost-every-kid has a device days. He was amazingly focused.

When we finally sat down to eat lunch together, I asked him if he liked school. I will never forget his response in a somewhat agitated voice. “I hate it here. Kids here don’t like to fight. They won’t fight. I like to fight.” I smiled because we were a school that used Glasser’s control theory as a philosophy to underpin community values. Our kindergarteners began early with conversations about solving problems with others by using words. It worked in the sandboxes and in their kitchen center. By the time our kids were nine like this little boy, they might roughhouse a bit on the playground but they, in general, just weren’t physically aggressive with each other unless someone really lost it.

I asked him why he liked to fight and he went back to wandering my office. No answer. I was ignored. Was he rude? Not really. Just not willing to talk about something that likely made him uncomfortable. Then he turned. “I like to fight because it makes me feel good. That’s why.” It’s all he said. I filed it away. There was no need to share it with the psychologist he saw every week. We all knew that anger was his weapon and his tool to escape class, the playground, the cafeteria – anywhere he felt unsafe. Especially foster families.

I came to value this nine-year old boy. His story has stuck with me for a very long time. I can still see the dusting of freckles on his nose, his darting blue eyes, and his pale arms learning against my desk as he typed away, standing at my desk. He was with us for three months and then disappeared into the lost world of foster children. We got a call from his next school asking about him and what we’d done that had worked since his grades were better at our school than anywhere else in his record. Let me be clear. We weren’t perfect for him or with him. I’m not laying claim to any savior mythology. But, I think we understood what he needed from us, mostly, and we didn’t need impulsivity test data to tell us that. What we did need was what we valued as a staff in our work with all our kids – a sense of empathy, trust, and respect.

We didn’t have much to share with the counselor who called. He’s smarter than his past files show, we said. He loves science and experiments. He can write poetry when he wants to. We shared that he was pretty well-behaved while with us other than the time he pushed an assistant while getting off the bus one day. Angry. Who wouldn’t be, we asked?

I’d never give that little boy Duckworth’s survey. It would only reinforce all the negatives in his life. And, I don’t think he lacked self-control at all. Every seemingly impulsive action he took – from his anger to his distractedness – was motivated to give him space to breathe and control over a world gone awry.

I still wonder, when I think of him, where he is today. I like to imagine that he found the perfect family and went on to graduate from college, maybe a science major. I like to avoid thinking that he’s in prison or dead. However, my dreams and my nightmares are both possible. I do know this. He was one of the most resilient little guys I ever knew. I didn’t expect him to focus all the time on school work, to become a model student holding on to his bootstraps. Instead, I expected him to find some slack with us, a little safety valve of a school where he could find relief from what Paul Tough reports from medical research as allostatic stress – a huge interference with a child’s working memory.

Finally, I’m not a fan of Angela Duckworth’s references to Sir Francis Galton. This little boy was the kind of child Galton demonized in his Victorian Eugenics pseudo-science. He could have been the poster child who the Commonwealth of Virginia sterilized under its Eugenics Laws, and he was the kid we could have handled in very wrong ways through the systems we employ to label children such as him because of his learning gaps, behaviors, and personality.

I feel this way about Duckworth and her Grit surveys because ethically I don’t like seeing Sir Francis Galton, father of the Eugenics Movement and social Darwinist, cited as a rationale by any modern-day researcher in regards to children and schooling. There is no good reason. It’s that simple to me.

While reminiscing tonight about the grittiest 9-year-old I ever encountered, it was as if he reached out to remind me today why I feel the way the I do. And, I remember good times with him that transcended his anger, distractedness, and lack of focus. I remember him well.

That was moving Pam. I found myself reflecting about challenging students I’ve had for the last 15 years. I remember them all by name, face and passion. I love your honesty…you put him with your best teacher, you didn’t share all the information and you took time to simply listen. I would bet you and your school offered the boy exactly what he needed. Patience and Caring.

Thank you for sharing Pam, your post produced, thought and reflection. It also made me ponder, could I be doing more for some of our challenging students? I always believe we can do more…its just not always clear what that actually is. It sounds as though you put in layers of support and took things one day at a time. But more importantly you CARED for him…and that is what he needed more than anything.

Thanks for sharing Pam.

-Ben

Ben,

We become so focused on what we need to do to ensure academic success for all the wrong reasons that we forget the kid inside the child’s body. I wanted to remember what it feels like to not worry about tests but to worry about the child. As for grit, I imagine that kid had developed more to get up every morning and keep going than almost anyone in his life. When I read Duckworth’s kid survey, I realized it was aimed at assessing compliance not resilience. I originally laughed at her 12 item survey because it struck me as the latest example of pop psych turned educational program. All it needed was corporate shrink wrap and a ted talk. Nothing wrong with making sense of practices that help children develop resilience. Nothing right about putting Galton’s name anywhere near children. That’s my problem – that in the instance of Duckworth is an indicator of a a a core belief about humans that I can’t abide.

Fascinating story, Pam, and I can empathize with your position.

Can you tell me how schools are using Duckworth’s Grit surveys? Have you seen them being used to determine placement?

Darren,

I was surprised when I went to Ms. Duckworth’s site to find the student test – 12 questions – and then to read the items. I worry about the misuse and abuse that will occur as these tests at her site become tools for educators to use to “assess” grit and impulsivity in children. What bothers me the most is the use of Francis Galton in her work as a rationale for her research statement. It’s unconscionable to me for an educator to do so knowing the damage to which he contributed in this country through the Eugenics Movement. I don’t know any schools specifically using that test but it worries me that some will.

This is such a wonderful post, Pam. Your decision to put this boy with the best teacher you had was not, as I’m sure you know, standard operating procedure in most schools. Generally, the more successful students – the most disciplined, eager, curious children – are placed in classes led by the most gifted teachers. The troubled, difficult, lower performing students get the “slow to grade essays” teachers, the faculty lounge complainers, or the first year newbies. And the kids know it; they quickly learn where they and their teachers exist on the school totem pole. Your act told this boy that he and his learning mattered.

Inspired by your post, I checked out Duckworth’s 12-Item Grit Scale. I’m not sure I understand the value of this scale. So, if I come out fairly soft and distracted, what happens then? Hannibal Lecter and Mother Teresa would come out pretty gritty, but what does this scale really tell us about how individuals will fare in the world and how well we will fare with them in the world?

I like what Alfie Kohn had to say about the value of developing grit in last week’s NPR article, “Does teaching kids to get gritty help them get ahead?” – “If there’s a problem with how kids are learning, the onus should be on schools to get better at how they teach — not on kids to get better at enduring more of the same.”

It seems to me his argument could be extended further to issues of inequality. Instead of focusing on how to get our kids focused and in line, wouldn’t it be better to pursue an agenda that ensures that their hard work actually has a chance of paying off?

Holly – glad you checked her page out. If a kid is going to score high in impulsivity based on that scale I bet teachers and parents already know that. I think Alfie K got it right. Thanks for your comment – so reflective.

I had to remember to breathe when I read your post. I taught two short years a long time ago but have the most vivid recollections of my students like the one you describe. While I am not in the classroom at this time, I am so fortunate to be working with a group of parents and friends who care just as deeply about these kids – and public education – and are trying to find a way to enable all kids the space and tools to truly learn… whatever those tools might be. It is these memories that keep me going, alongside blogs like yours that articulate so well the differences between a number of narratives (grit included) and their corresponding realities. Thank you for taking the time to share.

Katheryn

Kathryn,

Thank you for taking the time to read this post. And for Remembering why educators do this work. Some learn in spite of us but it’s those who learn because of us who often keep us awake at night. This child and the one you thought remind us of that –

Pam

Wow, brought me to tears. This little guy reminds me of one who came to our school as a 5th grader and spent the whole year in my classroom. I still have the note his mom wrote me at the end of the year. I also still remember the teacher next door telling me she wasn’t going to walk on eggshells around ‘that kid’ when I asked her to cut him some slack.

Your description of the anger hiding the fear is something so many forget in the course of teaching the standards not the student.

Thank you for being so honest.

Jennifer

Dear Jen,

So many educators “know” this child whether at 7 or 17 – it’s teachers such as you who remind all of us to look inside ourselves and each child – to find the person who may be hiding for good reason. Some children learn regardless of the teachers they have but your fifth grader had a chance to learn, be safe, be valued because of you. I thank you for that.

Pam

The word “eugenics” is unfortunately used in two very different ways: positive or voluntary, and negative. Galton’s involvement should not be conflated with policies and practices in Virginia’s history. Simply put, one who suggests aristocratic women marry early in life does not fall into the same lot as those performing forced sterilizations through the 1970s. Galton is not Goddard. Further, Galton did pen “Vox Populi.”

Ted,

Thanks for commenting- I spent extensive time learning about the Eugenics Movement about ten years ago thanks to my son who ended up with a National History Day documentary first place award on Eugenics in Virginia. It was a learning experience sitting through his interviews with Paul Lombardo at UVa, Mary Bishop, Pulitzer Prize winner for her investigative reporting and reading more primary source documents than I could have imagined – what started as a simple effort to support a couple of high schoolers turned into an educational experience of my own curiosity. While Galton, know as the father of Eugenics, was not connected in time to the negative Eugenics of Virginia and many other states, his philosophy gave rise to the dark side of it. My biggest issue is the use of Galton by Duckworth as a rationale for her “research” on grit as it is being applied in schools. I’m not a fan of Eugenics ala Galton or Social Darwinism as it on occasion is used to justify why some kids – particularly those representing opportunity gaps are labeled as lacking or needing more grit to be successful in school. In my experience, some of the most tenacious kids I know come from poverty – even if the “grit” survival skills they’ve developed may actually be seen as negative in school. I also note that often kids who are successful benefit from slack and abundance afforded them from their family situations. Duckworth’s use of Galton as a rationale bothers me.